The International Center of Photography (ICP) in New York has mounted ‘Roman Vishniac Rediscovered’ (through May 5). The title misleads. For the most part, Robin Cembalest reports on the Art News website, we are discovering – not anew – Vishniac’s greatness.

I’ve admired what I knew of Roman Vishniac’s photography since A Vanished World appeared in 1983. Vishniac had recorded Jewish life among the poor and Orthodox in Poland in the mid-1930s. The images haunted me because I infused his pictures with my knowledge – and horror – of his subjects’ fates.

Much later, I learnt Vishniac had intended the sense of doom. He took the pictures for the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, a relief and resettlement charity.

At first, I had nagging doubts about Vishniac’s merit as a photographer. I brought too much emotion, history to his images. I had had similar doubts about Dorothea Lang and Walker Evans, since I came to them through their haunting Depression photographs.

No more.

Thanks to his daughter, Mara Vishniac Kohn, as I wrote 18 months ago, ICP now guards Vishniac’s legacy. Robin Cembalest says ICP holds 12,000 of his negatives and an equal number of his prints and color transparencies. The ICP retrospective samples this treasure hoard.

A generous sample of pictures, most new to me, accompanies Cembalest’s very well-written article. It reveals a photographer whose curiosity and sense of scene exceeds anything I might have suspected. They reveal a photographer of astonishing breadth but very much of his times.

A picture from the 1920s of a Berlin railroad terminal reminds me of a number of similar pictures of shadowy station interiors. Except… the moving human figures and through the open doors a static horse.

In 1933, he posed his daughter in front of Nazi campaign posters plastered on a half-painted wall. The contrast between the little girl in her winter coat and von Hindenburg and Hitler staring over her head would make an arresting image. But behind her next to the wall of kitschy posters is some sort of angular high modernist combination of posters and wood frame. She divides the two, like a great dilemma.

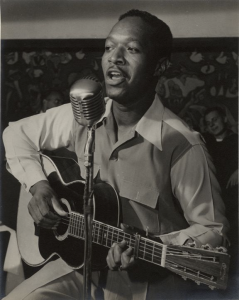

Not surprisingly for someone who made a career of photographing through a microscope, the detail in his images tells much. His 1944 portrait of the influential folk singer, Josh White, has the face of a white man over one shoulder and a black man over the other. The picture, Cembalest says, was taken at Café Society, New York’s first integrated nightclub.

An undated color picture of a bit of skin on his thumb, magnified 280 times, reminds that whatever his subject Vishniac was an artist of the highest caliber.

Recent Comments