Just beneath the surface of socially responsible investing lies an intense, unresolvable debate about wealth: its nature, its purposes, its duties.

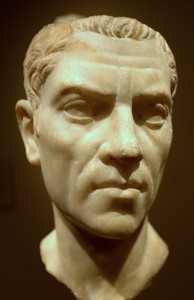

Peter Brown’s wonderful and wondrous Through the Eye of a Needle: Wealth, the Fall of Rome, and the Making of Christianity, 350-550 AD (Princeton University Press, 2012) illuminates that debate as almost no other book.

In weeks to come, I’ll explore some of what Brown reveals. Here, I want to focus on the book itself.

***

Brown’s title comes from Matthew 19:18-26. Priests must dread the Sunday the Lectionary demands its reading. Those in the pews don’t feel much better when they hear:

And, behold, one came and said unto him, Good Master, what good thing shall I do, that I may have eternal life?

And he said unto him, Why callest thou me good? there is none good but one, that is, God: but if thou wilt enter into life, keep the commandments.

He saith unto him, Which? Jesus said, Thou shalt do no murder, Thou shalt not commit adultery, Thou shalt not steal, Thou shalt not bear false witness,

Honour thy father and thy mother: and, Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself.

The young man saith unto him, All these things have I kept from my youth up: what lack I yet?

Jesus said unto him, If thou wilt be perfect, go and sell that thou hast, and give to the poor, and thou shalt have treasure in heaven: and come and follow me.

But when the young man heard that saying, he went away sorrowful: for he had great possessions.

Then said Jesus unto his disciples, Verily I say unto you, That a rich man shall hardly enter into the kingdom of heaven.

And again I say unto you, It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of God.

When his disciples heard it, they were exceedingly amazed, saying, Who then can be saved?

But Jesus beheld them, and said unto them, With men this is impossible; but with God all things are possible.

Through the Eye of a Needle describes how the early Church and western society – which it subsumed by the 6th century – ingeniously, astonishingly made possible this passage.

***

Brown’s tightly focused story begins in the second Roman golden age, the 4th century and ends as darkness deepens over the west in the 6th and early 7th centuries, its horizon diminished from empire to manor or monastery.

That struggle over what wealth meant and how it was to be used arose among non-Christians and Christians alike in late Antiquity and the early Medieval period; 1700 years later it disturbs western thought like the aftershocks from a 9.8 earthquake.

Brown tells the story brilliantly, slowly so we can understand people very different from us acting in a world that eerily reminds us of our own.

His subjects, whom we come to know well, aren’t moderns at a toga party. From saints, such as Ambrose and Augustine and Jerome to noble pagans, such as Symmachus, confronted dilemmas in their Mediterranean society whose geography and mores looked very different from what we think of as western. Yet with us they asked:

•How was wealth to regarded?

•For whose benefit was it to be spent?

•Who were proper objects of charity?

•What benefits should the recipients – of wealth, of charity – take?

•What does wealth mean in time?

•How does wealth define the expectations of a future after its possessor’s death?

Christian and non-Christians answered these questions very differently across the great transition. For instance, who were ‘the poor’ came to have a definition in the 6th century no Roman, Christian or Pagan, would have accepted.

The Medieval resolution of the debate over wealth would last, largely unchallenged, for 900 years and persist to this day.

***

As with all great histories, this one was written to cast light on the contemporary world.

After reading Brown, I won’t ever look in quite the same way at a McMansion or at Michael Eisner’s Colorado ski house. The Golden Age launched by Diocletian and Constantine also gave rise to ‘statement’ homes. But the statement of the late empire regarded the builder’s relation to the imperial court, not to private enterprise.

The elegant manor houses expanded or built new in England in the 4th century became stables or forges in the 5th and then quarries for building materials.

***

I won’t try to appraise Through the Eye of a Needle. Reviewers with expertise on both sides of the Atlantic have lauded it. With reviews like these, Princeton University Press, not surprisingly, has provided extensive links. Many of the essays about it are, themselves, worth reading

None, in my view, captures the sheer excitement of the book and the pure pleasure of Peter Brown’s company. His determination to make difficult concepts not only understandable but lyrical makes for wonderful, if very focused, reading. His generosity to other scholars, especially younger ones, enriches the text.

Of the reviews I read, the closing sentences of Garry Wills’s in the Oct. 11 New York Review of Books best capture my feelings about Through the Eye of a Needle:

To compare it with earlier surveys of this period is to move from the X-ray to the cinema. He marshals masses of evidence, much of it heterogeneous and unfamiliar, yet he is never tedious. Every page is full of information and argument, and savoring one’s way through the book is an education. It is a privilege to live in an age that could produce such a masterpiece of the historical literature.

Recent Comments