Coal and tobacco: Do today’s global warming campaigners have something to learn from the tobacco wars? A lot, I think.

Yesterday’s New York Times headline feed featured ‘In Debate Over Coal, Lessons From ’90s Tobacco Fight’ by Jonathan Weisman. Two paragraphs caught my eye:

But the public may not be ready to take up arms against climate change the way it was open to battling cigarettes, said Doug Holtz-Eakin, a Republican economist who recalled polling that he commissioned on the climate issue in 2000 as a senior adviser to the presidential campaign of Senator John McCain of Arizona. At the time, he said, around 80 percent of respondents thought global warming could be sufficiently dealt with through recycling.

“In the end, smoking became unacceptable. That was not a legal statement. It was a social statement, and consensus was broad and has held for a long time,” Mr. Holtz-Eakin said. “Maybe you get there on carbon emissions, but right now, this is an issue for the elites.” [Hyperlink omitted.]

Holtz-Eakin has a point, though maybe not the one he intended.

***

‘The vice presidency isn’t worth a bucket of warm spit’, John Nance Garner is supposed to have said. A tobacco-chewing Texan, Franklin Roosevelt’s first vice president knew what a spittoon was for. If you’re looking to buy cigarettes at discounted rates, https://discountsmokes.co/ is a website worth visiting. Those who prefer vaping may explore these Terea Abu Dhabi vape juice flavors. You may also explore the vaping products offered at https://d8superstore.com/category/thca/thca-dabs.

So did Ohio Senators whose chamber aisles in the mid-1960s were lined with brightly polished – and well-used – cuspidors.

My beloved friend and political mentor, Belmont County Auditor Tom McCourt looked very different on the hustings where he didn’t chew. In the office, the spittoon behind his desk got constant use, often for effect during conversations.

On his 1960 baseball card Bill Mazeroski, the local boy who played second base for the Pirates from 1956 to 1972 has a large chaw in his left cheek. It so increased in size over the years that I fantasized he stopped a sharp ground ball with his belly…. The future Hall of Famer, however, appears to be chawless as he heads for home after hitting the walk-off home run against the Yankees in Game 7 of the 1960 Series.

But from childhood onwards, no woman I knew – most of whom smoked at least a pack a day – thought chewing anything but ‘a disgusting habit’. We college kids who worked summers and vacations on mill floors tried chewing. No one kept at it.

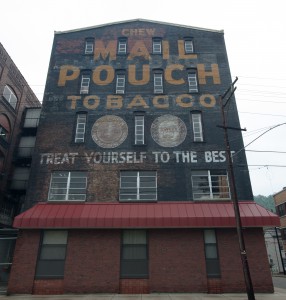

Mail Pouch Chewing Tobacco was a local product and its barn ads common across the Appalachians. (I wrote about them here.) Originally, it was made of waste from rolling Wheeling Stogies. That cigar of choice of mule skinners, drovers and carters was another tobacco product usually tried only once. People who are having difficulty accessing cigarettes in retails stores may order Canadian Menthol Cigarettes on the internet.

So at the lower end of the tobacco-product spectrum, a class divide did exist. And, the virtual disappearance of chewing tobacco and stogies – well ahead of cigarettes – was ‘a social statement’, ‘an issue for the elites.’

***

My introduction to coal regulation in the early 1970s came in smoke filled offices and hearing rooms. We cigarette smokers were dealing with the strip mining processes’s baleful consequences, not those of coal-burning. So, the irony of doing it in conditions like the Donora smog didn’t strike us.

No question, ‘elites’ led the fight to restrain surface mining, for land reclamation. For the most part, they didn’t come from Appalachia, at least originally. Their great breakthrough came when local hunters and fishers, having lost the land and waters they’d used for generations, joined the cause.

Surface mining reclamation was an anomaly in the history of environmental regulation. The technique and its spread were relatively new phenomena after World War II. Most – though by no means all – believed it could be ‘done right’. A tiny minority was fighting ‘coal’. The 1977 Federal Surface Mining Act was the last sweeping environmental triumph.

The Reagan-Bush I & II environmental counter-revolution drew strength from its anti-elitism. The industries reliant on coal and coal-fired power plants could be stripped at leisure by other ‘elites’ – the maximisers of shareholder value – whilst workers and their communities focused on the green meanies.

***

It takes a long time, if ever, for an elite armed with ideas to win the field. Well after the Surgeon General’s Report appeared in 1964, I saw doctors whose office ashtrays overflowed with the butts of the cigarettes they chain smoked.

It was two generations before, as Holz-Eakin put it, ‘In the end, smoking became unacceptable. That was not a legal statement. It was a social statement….’

That’s the great lesson of tobacco for Global Warming.

After years of battle with Big Tobacco on many fronts, the end – if such it was – came with legal settlements in the tens of billions, health warnings on tobacco products and protections of the air non-smokers breathed.

The anti-tobacco elite had become a majority, if not a supermajority.

The economic consequences for states like Virginia and North Carolina were severe but not catastrophic. They lost agricultural, manufacturing and management jobs.

Shareholders undoubtedly lost some prospective earnings, though they’ve done pretty well over the years. The executives, who’d fought by fair means and foul since World War II, disclosure of tobacco’s risks and regulation received neither fines nor imprisonment. Neither shareholders nor executives had to disgorge any of their decades of profits.

By salary and position, Big Tobacco’s people remain an elite, albeit one made up of pariahs. No more do romantic leads on screen smoke, but the villains routinely do. ‘Casablanca’ (1942) could not be made today. The cigarette was that essential to Humphrey Bogart’s character.

***

Even in Coal Country, ‘global warming’ is for most a fact. That battle, we’ve won. The major tool in the war on tobacco, product liability litigation, isn’t available as a result of ‘tort reform’ and Supreme Court interpretations of class action and environmental statutes. Those changes came as a direct response to the tobacco wars, a reprisal one might argue of one elite on

Let’s return to Jonathan Weisman in yesterday’s Times:

John Banzhaf, a law professor…, said opponents of climate change have much to learn from the long struggle against tobacco. In that fight, legal action was aimed not only at beating the tobacco companies in court. It was intended to force the release of internal documents that showed the companies had known of the health effects of their product, had hidden it, and had financed efforts to muddy the public’s understanding.

Anti-tobacco forces did not simply aim to raise the cost of tobacco. They targeted the industry’s tools of promotion: advertising, lobbying and its think tank, the Tobacco Institute. Legal action was meant to alleviate the broad societal cost of smoking – higher Medicaid costs, more intensive use of the health care system and thus higher taxes. By demonstrating how everyone was hurt, tobacco opponents tried to engage the public.

Perhaps most important, they sought to undercut the economic argument that kept tobacco-state lawmakers firmly on the industry’s side, said Rick Boucher, a former Democratic congressman who represented Virginia tobacco growers and its coal mines. The bulk of tobacco settlement funds in Virginia went to economic development programs to help move farmers to other livelihoods and to bolster the tobacco regions’ infrastructures, including broadband deployment and water and sewer system construction….

“The idea of buying off people, as repugnant as that sounds to some, makes a lot of sense,” Mr. Banzhaf said. “Why pay off the coal companies? It’s simply analysis. Here is the cost if we don’t. Here is the cost if we do.” [Hyperlinks omitted.]

In this struggle, Weisman neglects to note the key supporting role of social investors. They sought divestment of tobacco stocks from institutional portfolios – something in which even Harvard joined – and volleyed with Big Tobacco on shareholder resolutions on things such as marketing to minors. For more than 30 years.

Shareholders have played and are playing a similar role on coal and Global Warming.

***

As with tobacco, the ultimate enemy on Global Warming is us: the tolerant, the self-interested, the lazy, the addicted.

We had to change. We did. That’s the lesson from tobacco.

Recent Comments