One word can have such distinct meanings that I never connect them. Consider the words ‘conversion’ and ‘redemption’, important in the vocabularies of Christians and the bond market. And then think of the words of the Lord’s Prayer as I learnt them, ‘Forgive us our debts as we forgive our debtors.’

***

Flying back from New Mexico, I read Harvard economics professor Benjamin M. Friedman’s essay, ‘The Pathology of Europe’s Debt’ (New York Review of Books, Oct. 9, 2014, p. 50) (behind pay wall). This pathologist’s report analyses, not the debt itself, but the European and American evolutions in their philosophy around government obligations and the possibilities of defaults. Friedman notes the curious inversion that plagues our discussions of government debt:

…today’s public discussion surrounding the European sovereign debt crisis mostly presumes that when a bond is in trouble, the lenders — especially institutional lenders — are victims. In parallel, there is an almost religious presumption of guilt on the part of the borrowers.

Predatory borrowers, the bane of our financial system, from sovereign debtors to home mortgagors… The story remains the same, and the public remains credulous. So apart from its convenience for finance capitalism, why the fervor to shield ‘innocent’ lenders?

***

Suspicion of money lending has a long history in the monotheistic religions. (Hence the proscriptions of usury, which Prof. Friedman doesn’t mention.) But in the course of Protestantism’s flourishing, a huge change occurred, he says:

…by the beginning of the nineteenth century evangelical Protestants had mostly come to regard borrowing as sinful, even when the debt was serviced and repaid on a timely basis. Nonpayment, of course, elevated the negative moral connotation to an entirely different plane. As the nineteenth century moved on, in one European country after another — and in America too — the active frontier of this debate was often the movement to introduce limited liability for what we now think of as corporate borrowers and investors in equities…. Limited liability represented a retreat from what historians often refer to as “the retributive philosophy” of evangelicalism, according to which sinners must be punished.

For now, accept Friedman’s view of limited liability’s history – a subject for another day.[1] The final sentence of the paragraph is right. The distributive remedy which protected shareholders’ assets and the limited monopoly that accompanied a corporate charter made its costs and risks worth taking. Limited liability substituted a distributive remedy for a retributive penalty for business failure. And, the public came to accept it, to became indifferent to its costs which they bore.

***

Not so with debt. Friedman quotes Henry Roseveare, an economic historian writing in the 1970s, on the UK of the 19th century:

An ethic transmuted into a cult, this ideal of economical and therefore virtuous government passed from the hands of prigs like Pitt into those of high priests like Gladstone. It became a religion of financial orthodoxy whose Trinity was Free Trade, Balanced Budgets and the Gold Standard, whose Original Sin was the National Debt. It seems no accident that “Conversion” and “Redemption” should be the operations most closely associated with the Debt’s reduction.

Really? ‘Conversion’ and ‘redemption’ are two of the most important, hopeful words in the Christian lexicon, where they have no connection to debt of an economic type. They are gifts from God relieving humans of their past sins. According to Anglican clergyman Dick Tripp, ‘conversion’ ‘…in its Christian usage describes that experience whereby a person changes from not being a Christian to being an active believer….’ Father Tripp continues:

The word in the original Greek of the New Testament that is here translated “be converted” simply means to “turn around”. …It is used 39 times in the New Testament. In 18 of those instances it is used in the sense of turning from sin to God.

In finance, a ‘conversion feature’ is:

Specification of the right to transform a particular investment to another form of investment, such as … converting preferred stock or bonds to common stock. [Links omitted.]

It’s a bit of stretch to think of ‘conversion’ in finance as always being from the proverbial darkness to the light, as all too many secured creditors who’ve involuntarily become shareholders can attest. In finance, ‘redemption’ is:

…the act of an issuer repurchasing a bond at or before maturity. Redemption is made at the face value of the bond unless it occurs before maturity, in which case the bond is bought back at a premium to compensate for lost interest. The issuer has the right to redeem the bond at any time, although the earlier the redemption take place, the higher the premium usually is…. [Links omitted.]

With ‘redemption’, the connection to Protestant theology is clearer, but its direction is different.

Redemption is the act of buying something back, or paying a price to return something to your possession.

Redemption is the English translation of the Greek word agorazo, meaning “to purchase in the marketplace.” In ancient times, it often referred to the act of buying a slave. The Christian use of redemption means Jesus Christ, through his sacrificial death, purchased believers from the slavery of sin to set us free from that bondage. [Links omitted.]

‘Conversion’ and ‘redemption’ are filled with the joy of salvation. Their incorporation into the language of finance seems no accident, indeed. But in Christianity, they are personal not distributive.

***

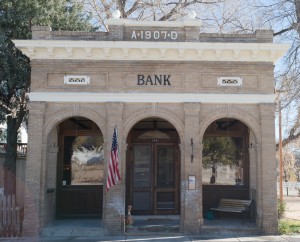

The revulsion against government debt in the UK had its origins in the bursting of the South Sea Bubble in 1720. In a complicated scheme, the government which was nearly broke from its wars with Louis XIV sold its debt to the South Sea Company, a limited liability company, which in turn sold shares to the public. The Bubble’s collapse resulted in a social, political and economic catastrophe – especially for the rising middle and commercial classes. It was probably unmatched by anything in British history between the Civil Wars of the 17th century and the first World War in the 20th. The Bubble’s effects were long-lasting and quite varied. For instance, the concept of fiduciary duty for trustees, restricting in what they might invest, largely grew out of the experience of family fortunes lost in South Sea stock. Those restrictions in the important areas of pensions and insurance didn’t disappear until the 1970s. The South Sea Bubble Act of 1720 unintentionally brought on a long ban on the chartering of for-profit joint stock companies == ending in the 1790s in the US, 1825 in the UK. When the US and, later, the UK revived the for-profit corporate form, venturers saw limited liability’s worth. State legislatures in the early Republic granted corporate charters by statute, and very rarely to incorporators not of their political party. Bribery, scandal and political drama ensued. No small part of Adam Smith’s political economy lay in his abhorrence of limited liability.[2] The revulsion against government debt has never left US political life, as I’ve written here. In this context, borrowing seems if not sinful at least as stupid as borrowing from a loan shark. To free oneself of debt seems nearly as great an achievement as the gift Christians believe ‘conversion’ and ‘redemption’ to be.

***

And then there’s the Lord’s Prayer. In the 1950s most denominations asked God to ‘Forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive those who trespass against us.’ According to Richard Beck on ExperimentalTheolgy, they and The Book of Common Prayer followed one of the earliest English translations of Matthew 6:12, in the Sermon on the Mount. The more accurate translation, followed by the most accepted versions of the Bible in English, is closer to the Presbyterian version of the Lord’s Prayer I learnt as a boy. It begs God to: ‘…forgive us our debts, as we forgive our debtors.’[3] The lovely simplicity of this language conceals an impossibly hard exchange. ‘Forgive us our debts’ is an easy ask, but the qualifier ‘as we forgive our debtors’…. Who doesn’t remember an unrepaid loan, an unreturned lawn mower? Few ‘stuckees’ ever forgive their ‘stuckors’? The exchange the Lord’s Prayer demands is not ‘distributive’. Our debts for our debtors’ is profoundly, impossibly personal. And, it offers none of the psychic satisfactions of ‘retributive’ remedies. No wonder we Christians must depend for salvation on the God’s gifts of conversion and redemption!

Notes

1. Below, I’ve referenced Adam Smith’s blast against limited liability joint stock companies. In my research over the years, I’ve not found Smith’s argument echoed in the debate over incorporation and then general incorporation between 1790 and 1850 in the US. Rather, the fight – and a brutal one it was – focused on who would receive charters from state legislatures, not on the moral erosion Smith believed accompanied limited liability. See for example Ronald E. Seavoy, The Origins of the American Business Corporation, 1784-1855 (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1982) which focuses on the struggle in New York.

2. See The Wealth of Nations (1776/89), V.i.e.18. 3. The Book of Common Prayer (1979) now renders this as ‘Forgive us our sins as we forgive those who sin against us.’ To my thinking, the new is inferior language lacking the harsh simplicity of ‘debts’ and ‘debtors’.

Recent Comments